Five Million Tonnes of Feathers Wasted! What To Do? /

It surprises me that little is done to use the millions of tonnes of the world’s chicken byproduct—feathers. For fifteen years I have read about optimistic research into how to use feathers in a productive way instead of sending them to landfills. Some farmers use them as low-grade feed but it is usually cheaper for them to just bury the feathers in a landfill. Researches have come up with many other ways to re-use feathers in industial processes but I can’t find any major way they are actually doing it on a big scale.

You can read about investigations into industrially processing feathers to form different kinds of plastics for uses from flowerpots to automobile dashboards. Or just made into plastic biodegradable pellets that can be made into many things. Just search, “industrial feather waste use”.

This truck full of waste feathers tipped over a few years ago on the highway north of where I live.

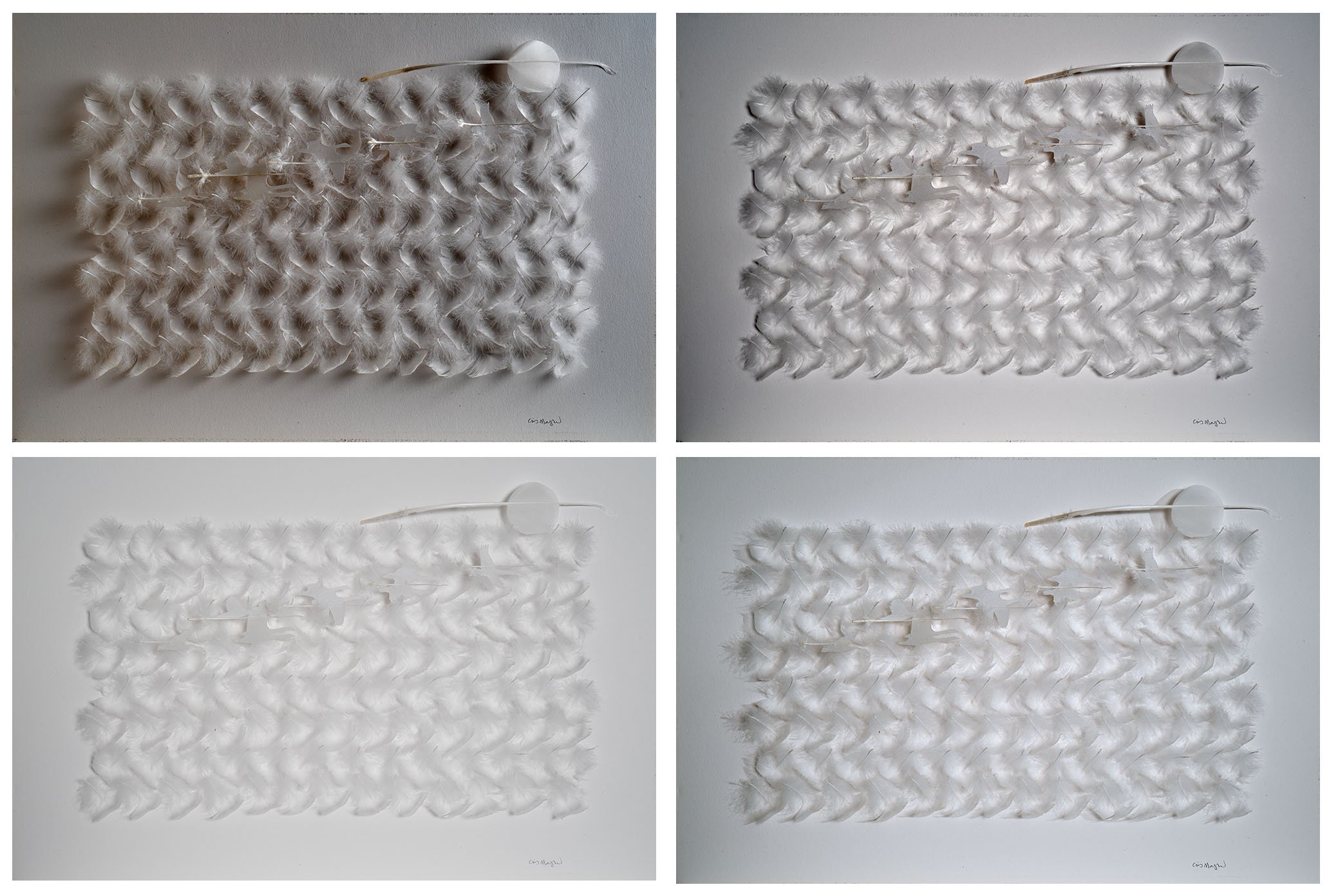

Stop Motion of a Large Piece /

Feather carving

In the stop motion video, you can see the progression of placement and cuts. For me, what really stands out is how the feathers and the cutout birds pop out at the end when they are elevated. The shadows give the work an added dimension.

A big piece like this usually comes after making several smaller pieces where the design concepts are tested. It took a while to collect enough of the right feathers—these are all from the right side of the wing of molluccan cockatoos. Some were shed from a pet bird over several years and some shed in a nonprofit rehabilitation sanctuary for parrots.

I often show a playful element in my work. Playfulness allows me to learn new things and skills without being too tense, like young swallows just off the nest learning to fly. They often play with an airborne feather (that I provide), catching it in their beaks on the wing, dropping it, and picking it up again and again. I bet they were enjoying improving their flying and bug catching skills.

This large almost five-foot piece will be for sale in Arts Council of Big Sky Montana at their February 2024 event.

Light a Fire /

Phoenix, female Red-tail Black Cockatoo tail feather

Phoenix . female red-tail black cockatoo tail feather

To make a fire, you can use a bunch of dry fluffy feathers as a fire starter. This worked almost as well as paper in my wood stove.

For most people, paper is easier to come by. But for me and say, a chicken farmer, feathers are a ready source. One caution: a lot of down feathers floating around as you strike a match could cause something like a slow explosion. If that happened, you might need to rise from the ashes like a Phoenix.

A Vegetarian Bird /

Singer, Embarrassed Goldfinch

Goldfinches are one of the most vegetarian of birds. They eat seeds mostly, regurgitating them to feed their young, pulling seeds out of thistles, and all sorts of plants. I watch them out my dining room window hanging rightside up and upside down on thin swaying stalks of seed pods of cornflowers. Reading about them, I learned a new name for their vegetarian style of eating: granivores.

This feather carving isn’t yellow! I couldn’t find an appropriate small yellow feather so I just used this one and called the bird embarrassed.

Terres, John K. (1980). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Knopf. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-394-46651-4.

Swiftest Flight /

Swiftly, Crowned Crane secondary wing feathers

The swifts are little jet fighters of the bird world. Kayaking down the Cispus River, I gazed at dozens of Vaux Swifts flying above me along the river corridor. That is, when I wasn’t avoiding boulders and white water drops. These bird grow wing bones shaped differently than swallows which they otherwise sort of look like. It makes them look like fast jets and they fly like it. And they fly high and for up to 10 months without landing, drinking, feeding, molting, mating, and probably sleeping on the wing. I read on BBC Science Focus that during a lifetime, they can fly as far as to the moon and back seven times!.

I returned from the river and made this piece. The birds move and turn so quickly, they seem to just disappear all of a sudden, much like the Starship Enterprise when it goes into warp speed.

Recycling Feathers /

Preen detail, Capercaillie tail feather

A cool thing about shed feathers is that they keep their complex structural integrity yet the bird that shed them has already grown new replacements so it doesn’t need the old feathers. They usually fall to the ground to feed small creatures that decompose them breaking the feathers into small components that can be used by plants as nutrients. Then the plants or its fruits and seeds are eaten by creatures like insect which the birds eat to grow their new feathers.

I recycle feathers into my art but it is only a matter of time (hopefully hundreds of years) before my art and the feathers in the shadow-boxes become small components of dirt to be absorbed by plant roots

Decompositional bacteria eat the feathers—even on feathers growing on live birds. They do it by using an enzyme (keratinase) that decays the keratin that feathers are made of. Fortunately for the birds, they can pretty much stop this degradation of their feathers from happening. Part of a bird’s feather care routine while preening is to rub and preen bacteria inhibiting oil that is produced by a gland near its tail on its feathers. When a bird preens in this way, it’s kind of like seeing actor George Clooney combing his treasured Dapper Dan hair gel through his hair in the movie, Oh Brother Where Art Thou.

See this write-up and more references for detail on feather decomposition by bacteria. https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Feather-Decomposing_Bacteria

What Is Up? /

Around We Go

I’ve been feeling disoriented when thinking about our concepts of Up and Down. We need to orient ourselves in the world in order to make sense of it. So we make up stories for how the world is. Like existence having an up and down. But it doesn’t. The earth turns around in space amid the solar system and galaxy amid multiple galaxies. Another story we could make up which could feel just as true could be that instead of standing on the earth, we are hanging upside down, pulled by gravity. Then the Earth would be up, where heaven resides and hell would be the space below: space. Imagine that. You might feel disoriented.

Disorientation can be a good thing because it lets us experience the world in a fresh way, perhaps encouraging a sense of wonder and curiosity

As I think of this alternate way of perceiving up and down, I wonder what a flying bird’s take would be. After all, they fly in more of a three dimensional space than us, but like us, always oriented by gravity. Do they worship the earth and think that is where they want to go after they die instead of up into the clouds? I mean, they already have access to the clouds, sort of. Maybe they know something we don’t about the nature of what it is like there. But then again, isn’t the idea of heaven our story also?

Like I said, thinking about this stuff is disorienting.

Changing Times /

Where I live is changing. For one, more people move here which means houses and apartments are popping up like mushrooms and cars crowd the roads, all making less room for wild. Because I am connected to this place, I notice what to many might seem like small changes. Thirty years ago, little herring would school under the Olympia docks at end of the Puget Sound, now named the Salish Sea. I used to catch resident king salmon that were feeding on herring underneath the docks. I don’t see the herring anymore. Instead a more pollution-tolerant fish called Sticklebacks schools in big numbers.

I adapted my art in the piece pictured in the header to this changing scene. The Red-Breasted Merganser, who has wintered here probably from time immemorial, also adapts. I don’t know if they even eat sticklebacks which are, well, stickley, as well as much smaller than the herring and other fish that they are known to eat.

These and other changes have me feeling like sort of an in-place refugee. I wonder if the Red Breasted Mergansers feel the same.

Without Feathers, We Are Naked /

reposted from 2019

I learned a new word: “Metalute”. It comes from the Mehinaku language, a tribe that still lives in forests of Brazil and means that one is naked unless wearing feathers. I first read about this in a New York Times article (great article on the transformative, talismanic power of feathers, August, 2019) that referenced the anthropologist Thomas Gregor. I found his Mehinaku paper (in Portuguese) entitled The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village that was published in 1977 and was able to sort of muddle my way through it with my Spanish.

What About Feather Colors? /

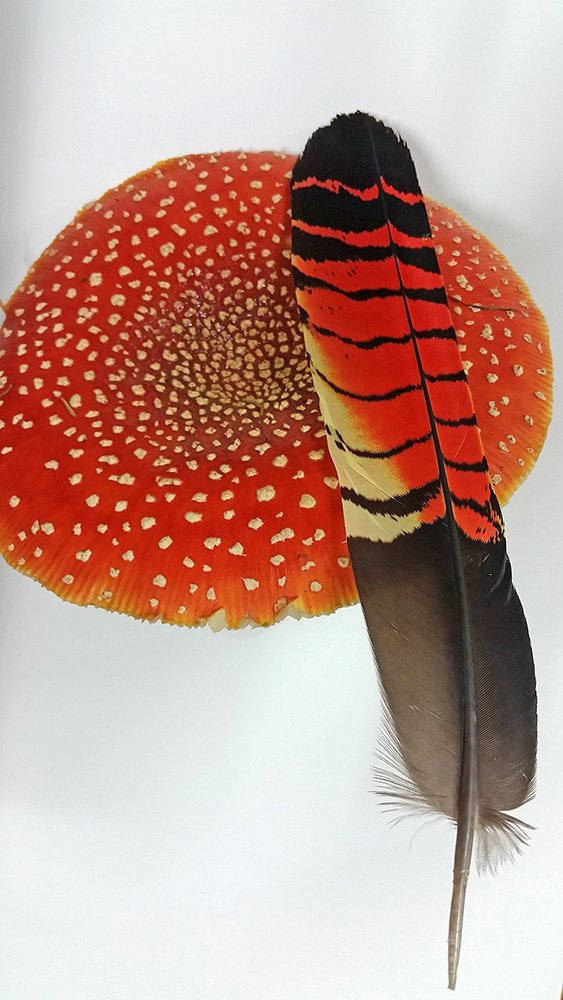

Bright reds in feathers come from what’s in the bird’s food. Carotenoid compounds give this feather its red and orange colors. Carrots have this, think carotene. though eating carrots doesn’t make your skin orange. Over eons, birds have learned to metabolize these compounds into their feathers to create orange, red, and yellow feathers. If we could make our skin different bright colors by eating things like carrots, our species would have a lot more skin variety that the browns, russet reds, and blacks. Instead, our duller skin pigments come from melanin which happens to be the same compound that most bird feathers are colored with. Interestingly, the earlier bird species like ducks and pheasants never incorporated carotenoids into their metabolism to make brightly colored red, yellow, and orange feathers; but later in evolution, songbirds, parrots, and other birds did.

How these mushrooms get their red color, I don’t know.

Amanita Muscaria mushroom and Red-tailed Black Cockatoo feather

Dinosaur Feathers /

Louse on a dinosaur feather preserved in amber

That dinosaurs had feathers was an abstract idea to me until I began looking at images of these feathers preserved in fossilized tree sap—amber. I wrote earlier about the term, pterosphere. It means the ecology of the habitat on a bird within the feathers, like beetles and mites that eat and decompose skin and feathers—on the bird. Well, dinosaurs had them too! Amber specimens show encased feathers complete with associated mites and beetles.

Witnesses to Life and Death /

Witnesses, 12 x 15 inches, Hornbill tail feathers

Trillions of cells are forming in the plants in my garden this Spring. It couldn’t happen without the many deaths of myriad plants and the tiny microscopic creatures that break down plant bodies into small stuff that the new growth can use.

I like to challenge my cultures tendency to avoid death, divorcing it from life by accentuating the break-down side of life in different ways in my art.

Feathers are lovely symbols of our aspirations like flight, hope, and achievement. They are also created because the birds that grow them killed plants and animals to eat to provide nutrients to the growing feathers. Personally, I find it wholesome and sacred to acknowledge this inherent folding of constant little deaths into our living. Like saying a blessing before a meal.

Recycling Feathers /

Each bird sheds hundreds of feathers each year. What happens to them? This small ant is repurposing this huge feather for something, I don’t know what. I stall the breakdown of a few shed feathers by recycling them in my art. But for most feathers, mites, fungus, and many other small creatures eat them, turning them into food that plants use. Birds eat the plants and fruits and bugs that eat the plants, growing more feathers!

Like Water Off A Duck's Back. /

A thin layer of air is trapped by the microsculptural bumps on ducks’ feathers making for a silvery sheen (called a plasteron) when feathers are dipped into water. It’s about surface tension. But if a bird dives deeper than several meters, the pressure of the water overcomes the surface tension, potentially soaking the feathers. But the feathers still remain dry! How? The ability to stay dry under the pressures of deeper water has to do how the birds’ preen oil changes the pressure needed to fully soak the feather. This allows deep divers’ feathers to just shed the water when the bird surfaces rather than getting soaked. *

Bird Crashes into window /

The Window uses a turkey and a swan feather

A songbird flies along on its migration at night. Like a moth at night, is attracted to light of a city. What looks like a clear way forward isn’t. This piece, the “Window”. was inspired by Miranda Brandon’s epic photographic series underscoring this threat.

What Do you Call a Feather in Different Languages? /

veer, pluim. Afrikaans

ريش, ريشة Arabic

хӏули. Avaric

tük, lələk. Azerbaijani

пяро́. Belarusian

перо̀, оперявам. Bulgarian

ploma. Catalan, Valencian

péro. Czech

plu, pluf. Welsh

fjer. Danish

Vogelfeder, befiedern, Feder. German

πούπουλο, φτερό. Greek

plumo. Esperanto

pluma. Spanish

sulg. Estonian

luma. Basque

پر. Persian

vuohiskarva, sulka, tyyppi, lehti, höyhen. Finnish

fjøður. Faroese

plume. French

pinne, plom, fear. Western Frisian

cleite. Irish

ite Scottish Gaelic

ague. Guaraní

પીછું. Gujarati

נוצה. Hebrew

पर, पंख. Hindi

toll. Hungarian

փետուր. Armenian

pluma, penna. Interlingua

bulu. Indonesian

plumo. Ido

fjöður. Icelandic

penna, piuma. Italian

נוֹצָה. Hebrew

羽. Japanese

wuluJ. avanese

ბუმბული. Georgian

қауырсын. Kazakh

ស្លាប. Khmer

ಗರಿ. Kannada

유, 깃, 종류, 깃털 Korean

pûrt, پهڕ, perr. Kurdish

plūma, penna. Latin

Fieder, Plomm Luxembourgish, Letzeburgesch

ຂົນ, ບິກ Lao

plunksna Lithuanian

spalva. Latvian

перо. Macedonian

өд, өрөвлөг. Mongolian

bulu pelepah. Malay

အတောင်. Burmese

pluim, veer, veder. Dutch

fjør Norwegian Nynorsk

fjær. Norwegian

atʼaʼ. Navajo, Navaho

ਖੰਭ. Panjabi, Punjabi

pióro. Polish

pluma, pena. Portuguese

pană, fulg. Romanian

перо́. Russian

pinna, pinnia. Sardinian

перо, pero. Serbo-Croatian

pierko, pero. Slovak

pero. Slovene

pendë, pupël. Albanian

fjäder. Swedish

nyoya. Swahili

சிறகு. Tamil

ఈకT. elugu

пар. Tajik

ขน, ขนนก. Thai

ýelek. Turkmen

balahiboT. agalog

tüyT. urkish

перо́. Ukrainian

پنکھ, پر Urdu

lông chim, lông vũ, lông. Vietnamese

plüm, bödaplümem, pen, bödapen, bödaplüm, plümem. Volapük

pene. Walloon

פעדער. Yiddish

羽毛. Chinese

uphaphe. Zulu

I copied this off a site called Definitions.net

These are not hearts! /

ruffed grouse body feathers

We make sense of the world through symbols. These are beautiful natural heart shapes but for a grouse, they are not likely symbols of love but useful for hiding, for camouflage.

108 Species of Starlings! /

Did you know there are 108 species of Starlings? Most live in Africa. The science names of the starlings that donated these feathers for what I call my "Starling Poster" are:

Lamprotornis iris

L. nitens

L. purpureus

L. elizabeth

L. chakrurus

L. australis

L. acuticaudus

L. purpuroptera

L. regius

L. splendids

L. shelleyi

L. superbus

L. purpuriceps

L. ornatus

L. hidebranti

L. muesii

Cirmyricinolu leucogaster

Orychognathus walleri

Peoeptera stuhlmanni

Saroglossa spiloptera

These feathers were originally used in an ornithological study of feather evolution and were obtained from the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Shadows /

Swan NIght Flight . Mute Swan body feathers

I owe a debt to shadows. Without them, my art would be flat and less appealing, poorer. As I think about this, I notice all around me the shadow of my fingers as I type on the keyboard; how the chair, the pencil, the wastebasket throw their bits of darkness to create a richer presence; that at night when the lights are off, I am enveloped in Earth’s shadow. I primarily work with feathers that usually symbolize the unshadowed part of existence like flight and air and light. Which is why shadows are so important in my work and life, to balance the light, the sky, and the heavens with the Earth and darkness.